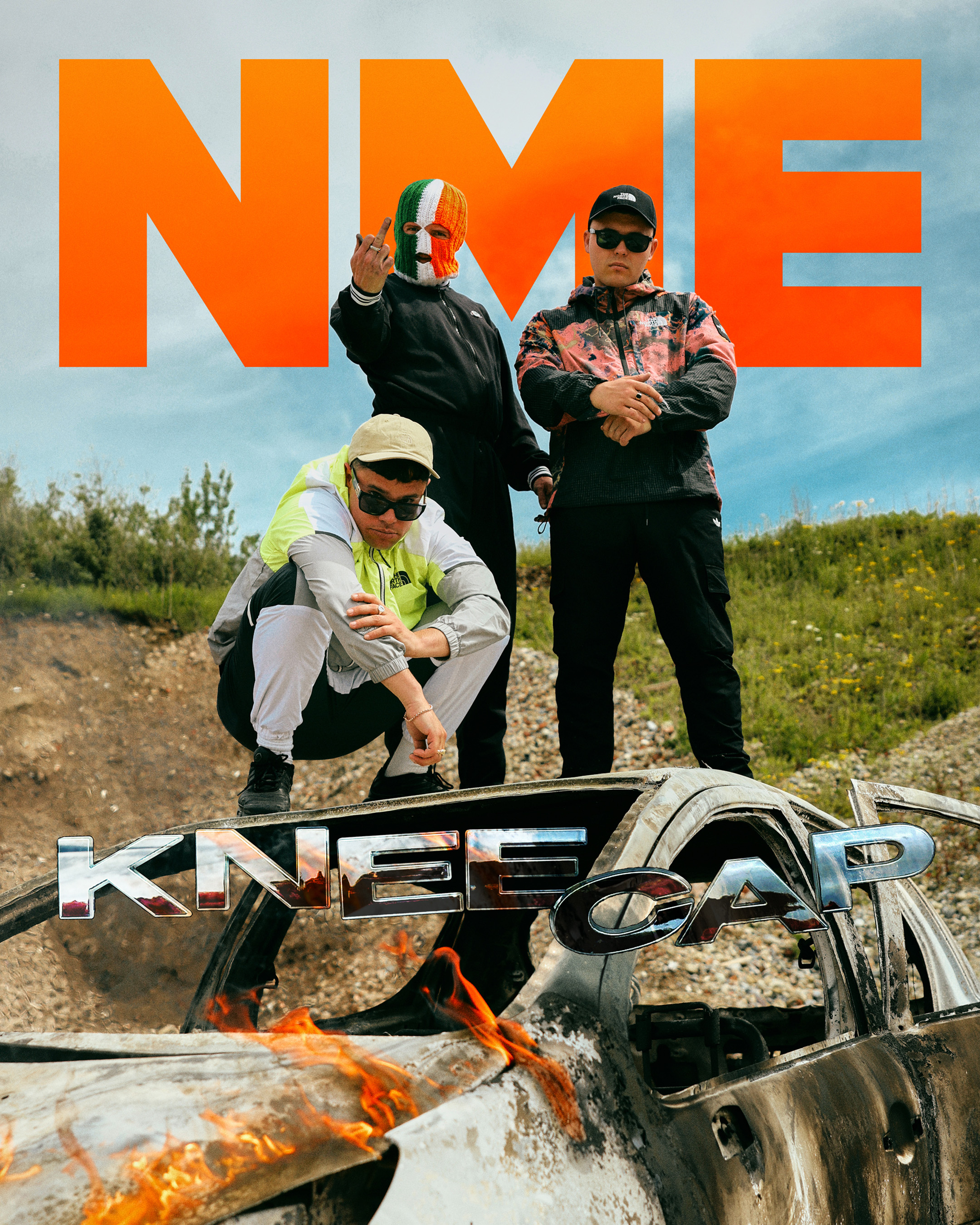

“Let’s set fire to it,” instructs NME’s photographer as Kneecap pose atop a burned-out car, much to the delight of the Belfast rap trio. “Can IIIIIIII doo iiiiiiiiit?” asks Móglaí Bap with all the glee of a kid wanting to lick the cake bowl. No, you can’t. Safety first, please – although someone on set may or may not have very briefly been singed (the first of many hot takes). “You wanna put some Savlon on that,” offers DJ Próvaí. “Savlon?” replies Mo Chara. “I thought that was a sausage you’s had over here!”

Previously condemned as a write-off, the car takes a beating as the band kick it to bits, pretend to drive it and jump off for a “Tom Cruise stunt roll” or two. This quarry not far from Plymouth is their playground for the afternoon. This is Kneecap: having a good time while spotlighting the hard times.

The title of Kneecap’s upcoming long-awaited debut album ‘Fine Art’ was their two-word response to the media frenzy that followed their 2022 unveiling of a hometown mural that showed a Police Service of Northern Ireland jeep on fire. “We knew that was going to have that reaction of people being really outraged,” Chara tells NME. “It’s such an extreme form of art through satire that it creates this dialogue where people start defending us or coming after us online. It’s hilarious that they’re so dedicated and they’re not even sure why they’re annoyed.”

At the heart of matter is their bewilderment at those more incensed by an image rather than the reality behind it. Próvaí (the chap in the tri-colour balaclava, satirically named after the slang for a member of the Provisional IRA) is quick to deny that Kneecap would ever promote aggression or stoke the flames of sectarian hatred, while also pointing out the hypocrisy. “If we were being sectarian against the police like some politicians said, then the police are only looking after one side of the community,” he says. “Otherwise, it wouldn’t be sectarian.”

Bap agrees: “It highlights the fact that we still have rocket-proof jeeps driving around Belfast and Northern Ireland in this day and age, after the peace process. Army fellas with machine guns. An act of violence is one thing, but the show of force with these jeeps is another form of that.”

Chara points out that they had “plenty of people at the mural unveiling who’d been in prison due to The Troubles and still had a great time and loved to see something artistic coming out of their once struggling community”. Sitting down with a few beers after the shoot, the band look at the burned-out car. What does an image like that mean to them?

“PTSD,” replies Bap. Chara continues: “We’ve seen it, but it wasn’t as widespread as it used to be. There wasn’t rioting with British soldiers still going on when I was growing up anyway.”

With its echo of their Belfast mural, this photoshoot too, the band argue, is just another work of ‘Fine Art’. “It’s a representation of our album,” says Bap. “It’s a metaphor.”

Every serious point is soon met with pub banter. “I used to date a girl called Simile,” chuckles Próvaí. “I can’t remember what I metaphor.”

“My wife left me because I couldn’t stop touching pasta,” adds Chara. “I’m feeling cannelloni right now!”

Even their dad jokes are lit. Onwards…

“For any language to survive, it has to be alive in the music” – Móglaí Bap

Kneecap are never far from controversy. Bap and Chara met while the former organised an Irish language festival where they’d meet DJ Provaí (then an Irish teacher, who would later quit after his school took offence at a Kneecap video that showed him with the words ‘BRITS OUT’ written across his arse). Chara (real name Liam Óg Ó hAnnaidh, 26), Bap (Naoise Ó Cairealláin, 30) and Provaí (JJ Ó Dochartaigh, 34) were raised speaking Irish in a country that didn’t want them to. They took to making music together in 2017 to tell real stories of their West Belfast lives and to hear their native tongue in something new and vital.

“There’s still a post-colonial hangover of colonisers telling us that our language is useless and that we’re not progressive,” says Bap. Provaí adds: “People have been told that for the last 100 years.”

They make their feelings on “colonisers” clear. In 2019, the band played a gig at Belfast’s Empire, the day after the Prince and Princess of Wales had stood on the very same stage. Rather than kowtow to Wills and Kate, the three Republicans started a chant of “Brits out”. “If you’re from Ireland, you understand that it means nothing to do with citizens or people who identify as British,” says Chara. “It’s a term used during The Troubles about getting the British government and British soldiers out of Ireland. That was it; it was a political thing.” The tabloids lapped it up, with The Daily Mail featuring their “balaclava-clad performance” with a line accusing them of “glorifying the IRA”.

The “very easily misunderstood” single ‘Get Your Brits Out’ followed, depicting a rager of night out with the Loyalist conservative DUP [Democratic Unionist Party]. “That was the idea: we’re getting the Brits out and giving them all ecstasy because they’re so stressed from complaining about gay marriage and stuff for so long,” says Bap. “They hate the gays, they hate dinosaurs,” continues Próvaí. “They hate everyone who loves a party, basically.”

Pissing off the right wing has become something of a hobby for Kneecap, who meet NME fresh from a North American tour. When they arrived for New Music festival SXSW (after the UK government withdrew arts funding to get them to get there; a legal battle is still underway), they joined a boycott after learning that the US military was sponsoring the Austin showcase festival. Standing against the “military industrialist complex” and in solidarity with Palestine, soon every Irish act pulled out. Texas governor Greg Abbott wasn’t best pleased, telling protestors: “If you don’t like it, don’t come here”. Kneecap’s response? “Suck our balls,” they told NME at the time. “Go see a concert instead of looking at guns all day.”

“I stand by that,” smiles Bap today. Próvaí, poetic and pragmatic as ever, adds: “You’ve got to know when to fold ‘em, know when to hold ‘em, know when to suck our balls, know when to run.”

“The movie needed to feel genuine – if it didn’t feel like something we would do, we just went, ‘No chance’” – DJ Próvaí

Kneecap have always made their stance against what they call Israel’s “occupation and genocide” of Gaza clear. They’ve helped raise nearly £100,000 for a volunteer gym in the Aida Refugee Camp in Palestine, and loudly broadcast their message via social media and high-profile TV appearances.

There was some confusion, then, when the trio didn’t join the boycott of over 100 artists of Brighton’s The Great Escape due to the festival’s Barclays sponsorship; the bank is accused of financial ties to those arming Israel – it says it’s merely “trading in shares of listed companies in response to client instruction or demand”. Our shoot takes place on the eve of TGE, with the band telling us they were opting for the Trojan Horse approach of showing up and taking a stand.

“If your income depends on this life and you’re a touring band, then everything’s connected to one of these companies in some way,” says Bap. “Ideally, if we had the money, we’d just boycott everything and sit in the house and tweet all day.”

Chara points out that “SXSW was obviously a completely different thing”: “That was the army sponsoring it, do you know what I mean?” As for The Great Escape? “We’ve met Palestinians as well who have said that they don’t think it’s fair that the burden is on the artist either. They completely agree: you go, you make your money, you say what you can. Would you rather be a martyr with no cause? No one’s gonna give a fuck if you pull out of this festival, lose money and de-platform yourself.”

That platform is about to get much bigger with the August release of their self-titled feature movie. The brainchild of director Rich Peppiatt and with Michael Fassbender playing Bap’s father, an exiled IRA member, the ballsy biopic is a runaway romp of sex, drugs, music and politics. A clash of 8 Mile and Trainspotting with a dash of Steve McQueen’s Hunger, it took home the Sundance Film Festival audience award in January. Kneecap’s performance couldn’t be more convincing – but then, they’ve already lived it. “It needed to feel genuine,” says Próvaí. “If it didn’t feel like something we would do, we just went, ‘No chance’.”

With thrills, pills and bellyaches, the film shows the band at war with both sides – the Belfast authorities and dissident Republicans – and makes a case for the Irish language in the modern world with existence as an act of defiance. Ultimately, it sums up Kneecap’s mission: being seen in a place that never wanted you to exist.

That defiance runs through the album, too. Produced by Toddla T and set in their “favourite wee, dark, dingy pub” The Rutz, the songs and skits follow the band’s history via the sounds, stories, characters and emotions of a West Belfast night out. “The whole concept of the album is that we never really did spend that much time in nightclubs, because we love sniffin’ coke and talking shite,” says Bap.

“Confidence gives you the opportunity to look inwards… Our generation has that opportunity to be introspective” – Móglaí Bap

There are the ravey hip-hop bangers you’ve come to know Kneecap for – but there’s a low to every high. “I’ve got a point to be proving to myself, sitting too long getting mouldy on the shelf,” they spit on ‘Sick In The Head’, while Fontaines D.C.’s Grian Chatten lends vocals to ‘Better Way To Live’: “I think all day, but when I drink I’m OK, it gets further away everytime I try to grab it”. The idiosyncratic Irish mental health crisis lingers. “When you go up, you’ve gotta come down,” says Bap.

Ultimately, The Rutz is a place where anyone is welcome as long as they’re not a twat. The blissed-out house of ‘Parful’ samples Dancing On Narrow Ground, a documentary which explores how ecstasy-fuelled raves brought Catholics and Protestants together in Ulster in the ’90s.

“It changed how they thought about different sides of the community,” says Bap, hoping their music can do the same. He remembers going to the Protestant area of Sandy Row in South Belfast one July 12 for the Orangemen’s Day celebrations. Approached by a group of Protestant lads necking Buckfast, he was at first apprehensive – until they started rapping the band’s debut single ‘C.E.A.R.T.A.’ at him. “I knew then that they didn’t give a fuck about the politics,” he adds. “People on the ground don’t hold that kind of resentment towards each other. They just wanted to have a shindig.”

Peace, protest and partying – they’re all in the mix for Kneecap. They don’t deny their history: “Obviously I can’t speak for what happened before me,” says Chara, sharing his sympathy for what past generations went through. “But we don’t support violence as that doesn’t make any sense any more.”

For the working class Irish, there’s more that unites them than divides them – regardless of faith or origin. Theirs is the generation stepping out of the shadow of generational trauma and post-colonial shame with an assured stride. To say that Ireland currently has a strong cultural footprint would be an understatement – they’re kicking doors down. “That’s why we’ve got all these class bands,” says Bap. Look no further than Fontaines D.C., Lankum, CMAT, The Mary Wallopers, Sprints and NewDad.

“Confidence gives you the opportunity to look inwards,” Bap says. “If you lack confidence, then you look outside of yourself to find it in other people and places. Our generation has that opportunity to be introspective.”

In 2024, you can be the flame without starting fires. Kneecap’s only weapon is their art. “If success is a means of getting the Irish language to new places, then that’s something we have to take on,” ends Bap. “For any language to survive, it has to be alive in the music.”

Kneecap’s ‘Fine Art’ is out June 14 via Heavenly Recordings. The film Kneecap hits cinemas on August 2.

Listen to Kneecap’s exclusive playlist to accompany The Cover below on Spotify and here on Apple Music

Words: Andrew Trendell

Photography: Joseph Bishop

Label: Heavenly Recordings